Cold plunges went from “weird athlete thing” to mainstream wellness ritual almost overnight. They’re in luxury gyms, backyard setups, and every other morning routine video. The promise sounds simple: feel better, recover faster, be calmer, maybe even burn more fat.

But before you buy a tub or try stepping into 45°F water, you probably have one big question:

Is cold plunging actually good for you, or is it just a trend that feels intense and therefore seems helpful?

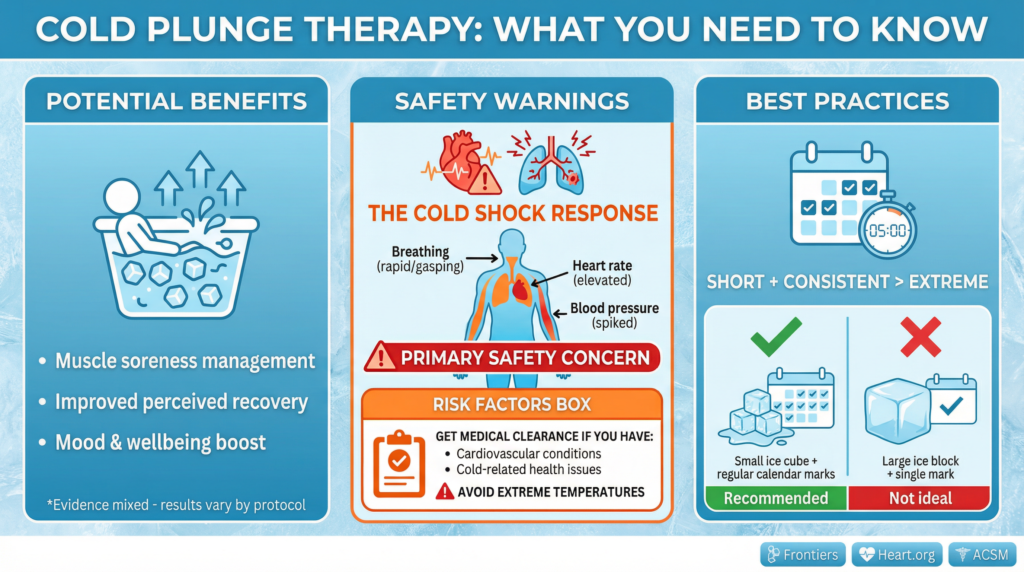

The truth is, cold plunging can help with certain goals and for some people, especially with recovery and mood. However, it also has real risks, especially for the heart and for people with some medical conditions. It’s also easy to overdo.

Let’s look at what happens in your body, what the research actually shows, where the hype gets ahead of the science, and how doctors usually weigh the risks and benefits.

What a cold plunge does to your body (the real physiology)

1) The cold shock response (why it feels so intense)

When you suddenly immerse in cold water, your body triggers a rapid “alarm system” called the cold shock response.

This can include:

- An involuntary gasp

- Fast breathing (hyperventilation)

- A spike in heart rate

- A jump in blood pressure

The American Heart Association notes that cold-water immersion can cause a sudden rise in breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure—and that the involuntary gasp can be dangerous if your head is under water.

NOAA’s cold-water safety guidance similarly describes cold shock, causing dramatic breathing and cardiovascular changes that raise drowning risk.

Translation: that “whoa” moment isn’t weakness—it’s biology. Your nervous system is flipping from calm mode into alert mode.

2) Blood vessel constriction → rewarming response

Cold exposure causes vasoconstriction (surface blood vessels tighten) to reduce heat loss. When you get out and warm up, you get a rebound rewarming/vasodilation phase.

This is one reason people report:

- A “buzz” or energized feeling

- Tingling as circulation returns

- Sometimes a delayed chill (more on this below)

3) The “autonomic conflict” (important safety concept)

Cold water can also trigger different reflexes at the same time, such as a “fight-or-flight” response along with a “diving response” (especially if you hold your breath or put your face in the water). Researchers have found that this overlap can sometimes increase the risk of heart rhythm problems.

This doesn’t mean cold plunges are always unsafe. It just means they aren’t a casual stressor, especially for people with heart or circulation issues.

Evidence-backed benefits (what may help)

Do ice baths help with inflammation and sore muscles?

The most consistent real-world benefit people notice is reduced soreness and a feeling of improved recovery after hard training.

Systematic reviews/meta-analyses generally find that cold-water immersion can reduce perceived muscle soreness and some markers related to muscle damage after intense exercise. However, results can be mixed depending on the protocol and outcome being measured.

A key nuance:

- Soreness relief is often more reliable than changes in inflammatory blood markers.

- Performance impacts can be variable (sometimes helpful, sometimes neutral).

If you train hard and want to feel better the next day, cold immersion can help, especially if you use it strategically instead of after every workout.

If you want a step-by-step setup (time, temp, and beginner progression), use this cold plunge routine guide:

Cold Plunge Routine: How Long, How Cold, and the Best Protocol for Beginners

Stress response & mood: Can a cold plunge lower cortisol?

Cold exposure is a stressor, so the topic of “cortisol” is often oversimplified online.

What the research supports more clearly:

- Cold immersion can trigger strong catecholamine responses (like noradrenaline/adrenaline) and measurable hormonal shifts.

- Some reviews suggest possible well-being/mood effects in healthy adults, but findings vary, and study quality differs across the field.

So does cold plunging “lower cortisol”? Sometimes people feel calmer afterward, but that’s not the same as “cortisol always goes down.” In many cases, acute cold exposure can increase short-term stress hormones, and you may feel good later as your body rebounds and you feel accomplished/energized.

Best way to think about it: cold plunging can be a controlled stressor that some people find mentally stabilizing—especially if they keep it short and consistent.

Circulation & “recovery signals” (without overpromising)

Cold exposure alters blood flow patterns and nervous system tone. That may contribute to:

- Temporary pain reduction

- A “reset” feeling after training

- Improved tolerance to discomfort over time

But it’s not a magic fix. You won’t “flush toxins,” and you can’t make up for poor sleep, inadequate nutrition, or an unorganized training plan with cold plunges.

Heart + safety considerations

Are ice baths good for your heart?

For healthy people who gradually get used to it, short cold exposure is usually safe and can be part of a broader routine for building resilience. The primary concern is the body’s immediate reaction:

Cold shock can sharply raise breathing rate, heart rate, and blood pressure.

That sudden cardiovascular load is exactly why clinicians urge caution for people with:

- Known heart disease

- Uncontrolled high blood pressure

- A history of fainting, arrhythmias, or chest pain

The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) also lists several contraindications and cautions for cold-water immersion in athletic contexts, including cardiovascular disease and uncontrolled hypertension.

Who should be cautious or get medical clearance first?

If any of these apply, it’s smart to talk to a clinician before doing true cold plunges (especially very cold water, full-body immersion, or solo sessions):

- Coronary artery disease, heart failure, prior heart attack, unstable angina

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- Known arrhythmias or history of fainting/syncope

- Raynaud’s phenomenon or severe circulation problems

- Cold urticaria (cold-triggered hives/swelling)

- Certain thyroid or blood disorders (ACSM notes examples like hypothyroidism and cryoglobulinemia in contraindication discussions)

Also, if you’re pregnant, have significant neuropathy (reduced sensation), or have a medical condition where sudden blood pressure shifts are dangerous, use extra caution and professional guidance.

Negatives and downsides people don’t talk about

Cold plunges get marketed like they’re free benefits with no cost. The “cost” is that cold immersion is a stressor—and sometimes it’s a stressor your body doesn’t handle well.

Common negatives people report:

- Numbness in fingers/toes (especially if too cold/too long)

- Headaches (cold trigger, breath-holding, tension)

- Lingering chills or an energy crash later

- Sleep disruption (some people feel wired; others crash)

- Skin irritation if the water isn’t clean/treated correctly

And there’s one more big one for specific training goals:

Cold plunges can interfere with strength/hypertrophy adaptation (sometimes)

If your main goal is building muscle and strength, doing cold immersion right after lifting too often might reduce some of the training effects. This is still debated and depends on timing, frequency, and your training plan. Sports science reviews discuss these tradeoffs and how results can vary.

Practical take: cold plunges are often best used:

- After endurance or high-volume sport work

- During competition phases

- When soreness management is the top priority

…and used more selectively right after heavy hypertrophy-focused strength sessions.

Who should NOT do cold plunges

If you want a simple “rule,” it’s this:

Do not cold plunge if sudden cold exposure could be dangerous for your heart, blood pressure, breathing, or ability to sense temperature.

Examples of “avoid or get clearance first” categories include:

- Significant cardiovascular disease or uncontrolled hypertension

- Raynaud’s phenomenon, severe circulation disorders

- History of cold injury or severe cold sensitivity

And regardless of who you are:

- Avoid breath-holding contests in cold water

- Avoid solo plunges in open water

- Avoid head-submersion early on (the involuntary gasp risk is real)

Why you might feel weird after an ice bath

If you’ve ever finished a plunge and wondered, “Why do I feel kind of off?” you’re not alone.

A few common reasons:

1) Adrenaline dump

Cold immersion can cause a strong sympathetic nervous system response. You might feel:

- Jittery

- Over-alert

- Emotionally “amped”

2) Breathing changes

If you hyperventilated or fought for breath in the water, you may feel lightheaded afterward.

3) Blood pressure shifts

Cold shock can acutely raise blood pressure, and the transition to warming can feel strange for some people.

4) “Afterdrop” (delayed cooling)

Sometimes your core temperature keeps dropping after you get out because cold blood from your arms and legs moves back to your core. That’s why you might feel fine at first, but cold and shivery 20 minutes later.

If you feel chest pain, severe dizziness, confusion, or you can’t rewarm—stop and seek medical care.

What doctors typically say about ice baths

Clinicians tend to look at cold plunges through a simple framework:

Benefit: “Can it help your goal?”

- Short-term soreness reduction and perceived recovery: often yes

- Mood/well-being improvements for some people: possible, still emerging

Risk: “Could this trigger a dangerous event in you?”

Cold shock can stress the cardiovascular system and breathing, causing them to work very quickly.

That risk rises if you have underlying heart/blood pressure issues or if you do extreme protocols.

So, doctors usually sum it up like this:

- Start mild

- Keep it short

- Avoid extremes

- Don’t do it alone

- Get clearance if you have cardiovascular risk factors

Quick FAQ (fast answers)

Is it bad to cold plunge every day?

For some people, daily cold plunging is fine. For others, it causes sleep disruption, excessive fatigue, or a constant “wired” feeling. If your recovery and sleep are improving, you’re probably okay. If they get worse, reduce frequency or intensity.

For a structured progression, use your internal link to the 30-day plan (e.g., /30-day-cold-plunge-challenge/).

Do you dunk your head in a cold plunge?

For most beginners, it’s best to skip dunking your head at first. Cold shock can cause an involuntary gasp, which is risky if your face or head is underwater.

If you want face exposure, build gradually (splashing, brief face immersion while seated, never breath-holding).

Key takeaways

- Cold plunges can help with soreness and recovery, and may improve mood or wellbeing for some people, but the evidence is mixed and depends on how you do them.

- The cold shock response is real and can put stress on your breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure. This is the primary safety concern.

- If you have cardiovascular risk factors or cold-related conditions, get medical clearance and avoid extremes.

- Short + consistent beats extreme for most people.